Currency Wars Part VI: Plaza Accord 2019

“We extend the analysis of the fixed price variable employment model with a brief discussion of the international implications of exchange depreciation and changes in net exports. We showed that a monetary expansion in the home country leads to exchange depreciation, an increase in net exports, and therefore an increase in output and employment. But our increased net exports correspond to a deterioration in the trade balance abroad. The domestic depreciation shifts demand from foreign goods toward domestic goods. Abroad, output and employment therefore decline. It is for this reason that the depreciation-induced change in the trade balance has been called a beggar-thy-neighbor policy – it is a way of exporting unemployment or of creating domestic employment at the expense of the rest of the world.

…

By contrast, when countries’ business cycles are highly synchronized, such as in the 1930s or in the aftermath of the oil shock, exchange rate movements will not contribute much toward world full employment. The problem is then one of the level of total world spending being deficient or excessive while exchange rate movements affect only the allocation of a given world demand between countries. Nevertheless, from the point of view of an individual country, exchange depreciation works to attract world demand and raise domestic output. If every country tried to depreciate to attract world demand, we would have competitive depreciation and a shifting around of world demand rather than an increase in the world level of spending. Coordinated monetary and/or fiscal policies are needed to increase demand and output in each country.”

Chapter 19: Trade and Capital Flows Under Flexible Exchange Rates

Macroeconomics, Second Edition

By Rudiger Dornbusch and Stanley Fischer, 1978

(Mr Fishcer Served as Vice-Chair, Federal Reserve From 2014 – 2017)

For the United States, the last two decades proved difficult from an economic perspective. Fundamental economic growth lagged behind levels produced for the prior 50 years. This, of course, related to the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO) that allowed Emerging Market (EM) Economies full access to Developed Market (DM) Economies without comparable access to their economies or any restrictions on their ability to manipulate the value of their currencies. With the resulting stagnation in real incomes for DM consumers as EM countries took a disproportionate share of global growth, anger arose against the elites who put such a system in place. This led over the past two years to significant changes in the political make-up of DM governments, that hitherto did little to change the rules of the game. With these changes in place and those on the horizon ahead, DM governments stand poised to alter these global arrangements that massively favored EM Economies over the past 20 years. And in doing so, the rules of the game will change significantly.

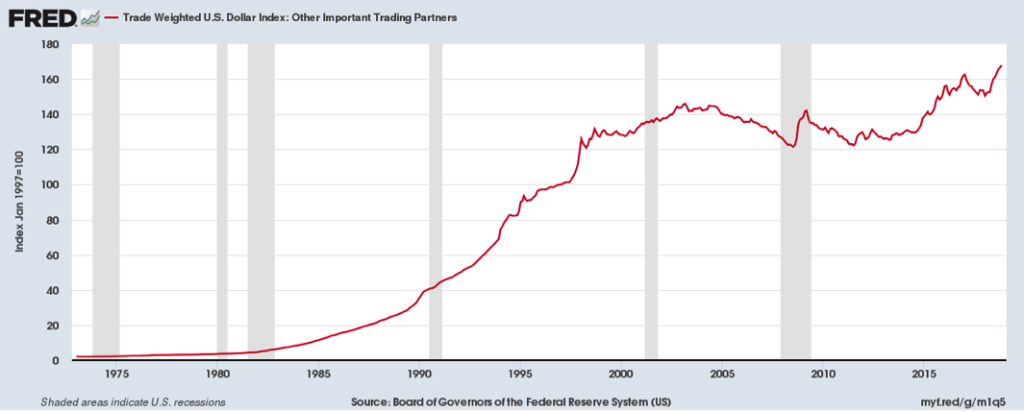

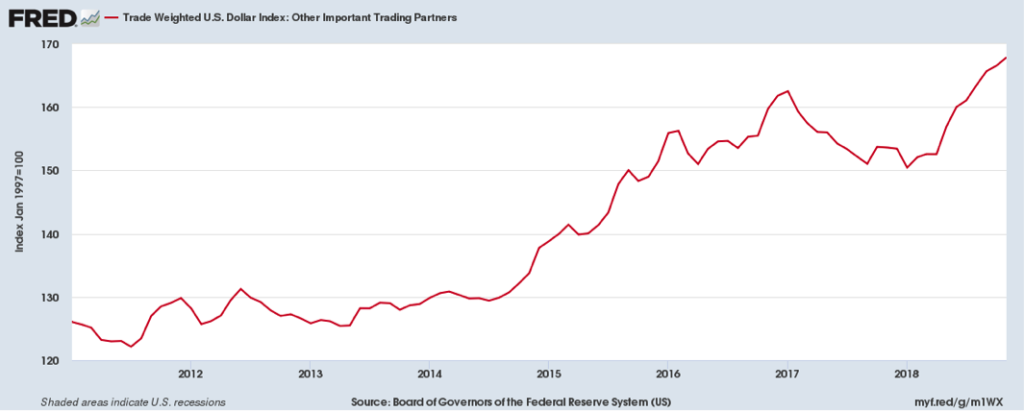

For EM Economies, depreciating their currencies proved the tonic to their economic growth issues. It produced hyper-competitive companies globally, enabling them to possess advantageous cost positions, and to grab global market share from established DM companies. This enabled their economies to grow at rapid rates, upgrading their industrial base and citizen’s income by leveraging access to DM consumer markets. The following chart demonstrates the massive drop in EM currencies against the US Dollar over the long term:

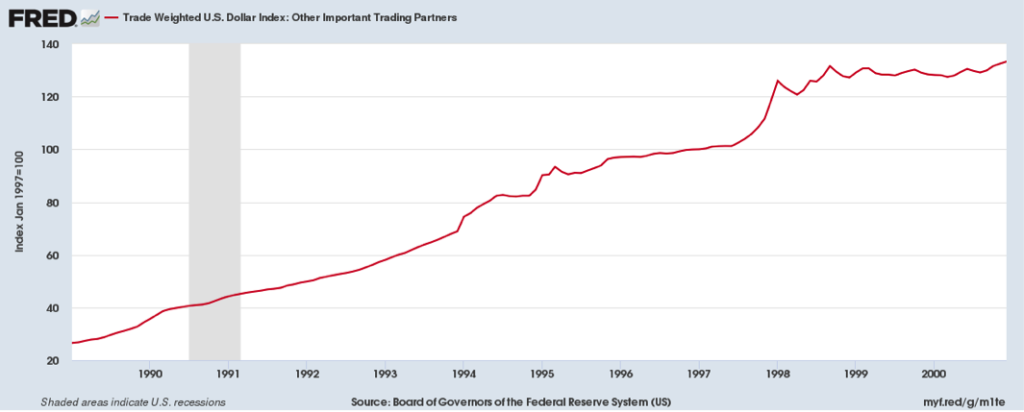

And the following chart focuses on the drop just from 1989 to 1998 in preparation for the commencement of trade under the WTO:

As can be seen in the chart, EM currencies dropped by over 80% from 1989 to 2000 as they positioned themselves for the WTO and access to new DM markets. This provided them many years of growth well above the levels sustainable with access only to their domestic markets. While countries such as Indonesia and Russia had currency crises in 1997 – 1998, as part of the Asian Financial Crisis, currency depreciation was steady over the decade as trade negotiations progressed. And countries unaffected by the currency crisis, such as China and India, took advantage of the turmoil to massively drop the value of their currencies. In addition to these currency moves, the EM governments limited access to their domestic markets, forcing DM companies to locate facilities locally and to transfer knowledge to local individuals and companies that would enable them to form competitive entities to the established players. This reinforced their growth, delivering levels even further above true sustainable growth.

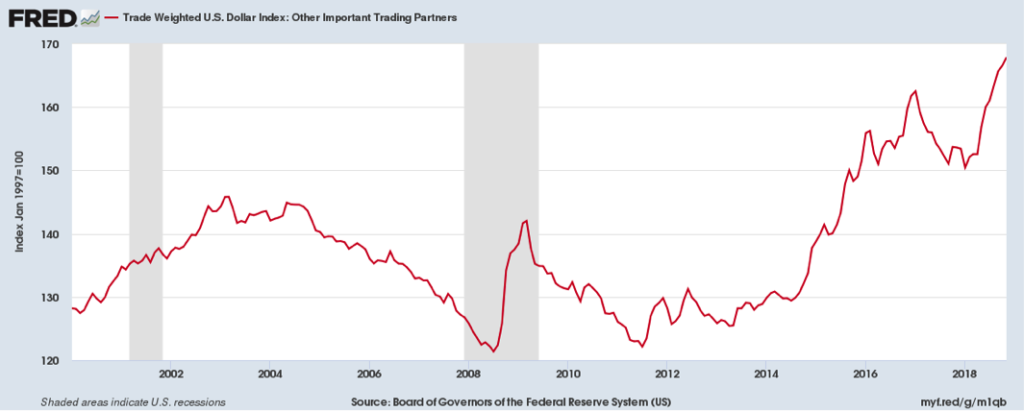

However, after almost 15 years of strong EM growth, growth began to stall around 2014. With the rapid growth came real inflation in costs which slowly made them less competitive with DM companies. In fact, Boston Consulting Group came out with a famous study in 2013 indicating that costs in India and many other EM economies now stood above those in the United States. To solve this issue and to reaccelerate their growth, the large EM economies began another round of currency depreciation in 2014, as the following picture demonstrates:

This ~30%+ depreciation of their relative cost base took these countries from costs 10%+ above DM levels to costs 15% – 20% below DM levels. This restored their global competitive advantage, positioning these countries for further growth at the expense of the DM economies.

However, for the DM economies, this created issues in delivering economic growth at levels that drove real incomes higher, after they just pulled their economies out of recession and began to grow again. In fact, for the United States, this depreciation created an Industrial Recession and a Nominal Growth Recession in 2015 – 2016. If the Industrial sector of the economy stood at its historical size prior to 2000 relative to the US economy, the US would have recorded an actual Recession.

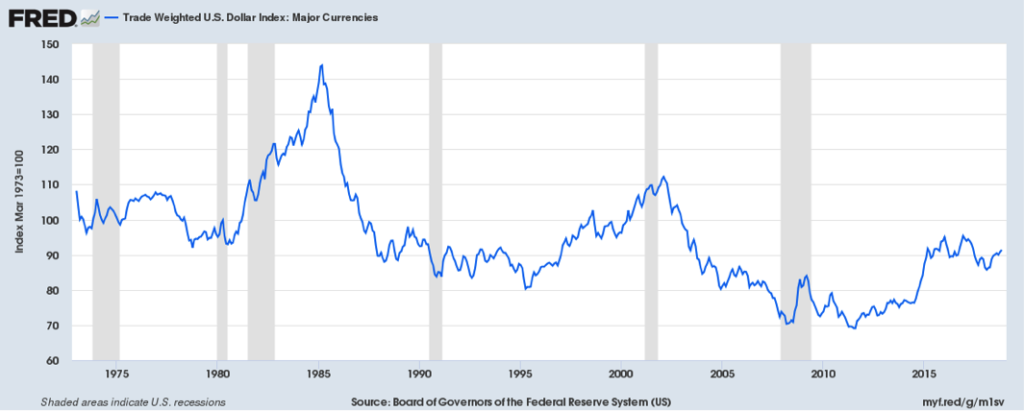

This issue stands in contrast to the DM currencies. If one looks at the DM currencies over time, their value has fluctuated within a band since the late 1980s. In fact, the value of the US Dollar today, relative to the basket of these currencies, equals approximately its value then:

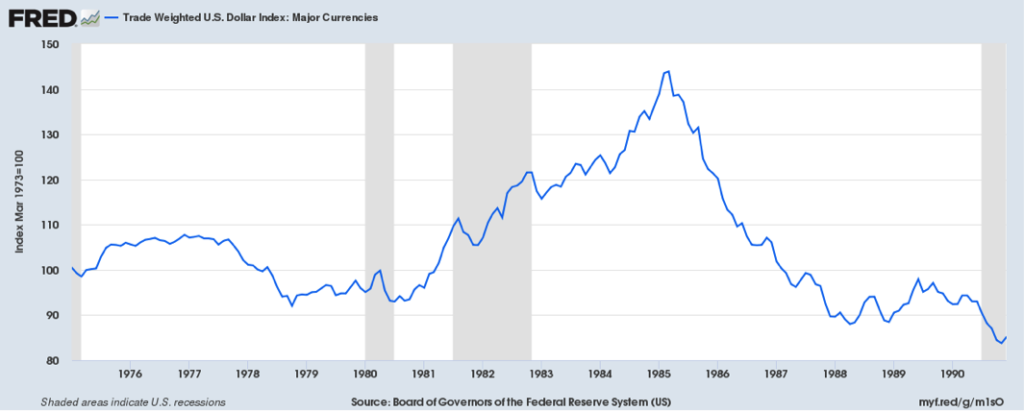

There is only one time frame when the US Dollar found itself outside this range, that occurred from 1981 – 1985, when the European countries depreciated their currencies against the US Dollar. This drove the US Dollar up 50% in value over just 4 years:

Ronald Reagan intervened in 1985 with the Plaza Accord in which these countries agreed to restore their currency values against the US Dollar in order to forestall actions that would have shut their companies’ goods out of the US markets. By 1988, the US Dollar returned back to fair value.

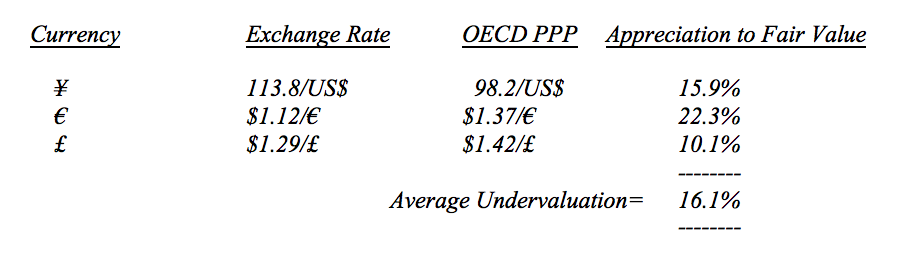

The OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) provides data on fair value of currencies using PPP, Purchasing Power Parity. (This data is available at www.oecd.org) This data makes clear the difference in the playing field between EM and DM currencies and what a manufacturer in the US or Europe sees when they attempt to compete globally against companies in the DM or in EM countries which have massively depreciated their currencies. Here is what the US manufacturer sees when he competes against companies in the DM:

While a US manufacturer may not jump for joy over this, the undervaluation of DM currencies sits well within the bands that have existed over the past 50 years.

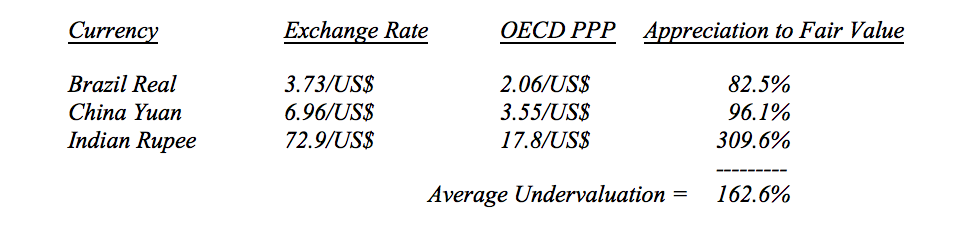

Here is what that same manufacturer sees when he competes against companies in the EM:

As the above table makes clear, the DM manufacturer sees a difficult to impossible situation. Competing globally becomes a non-starter when the EM manufacturer benefits from massive undervaluation of the currency.

With the US moving to reclaim its manufacturing from China to underpin its economic growth, China’s economy began to feel real pain over the past year. In order to offset the impact of the 10% tariff imposed by the US on $200 billion of its goods, China depreciated its currency 10% against the US Dollar. Of course, China exports over $500 billion of goods to the US. So, not only did it offset the tariff, it advantaged the other $300 billion in goods by making them an additional 10% cheaper. With the US threatening to impose a 25% tariff against all its exports, China indicated it would just depreciate its currency by 25% against the US Dollar. This action would force other EM countries to depreciate their currencies, lest they lose competitive advantage globally. For the US and the DM, this looks just like the runup in 1981 – 1985 in the US Dollar:

For the US, such an outcome in China’s favor, along with the EM, would become an unacceptable result. For Europe, which already saw a major slowdown due to the pressure on its exports, this would amplify the pressures building to tear the EU apart. And for Japan, which underwent a contraction in the economy in Q3, this would put acid on an open wound, harming its export-oriented economy. With all of the DM under tremendous economic pressure to raise living standards and grow their economies, the political will to intervene in the Currency Markets should manifest itself. For the first time since the formation of the WTO, the DM Governments would act collectively to prevent depreciation of the EM Currencies and to drive up their value towards fair value in a Plaza Accord 2019.

For a world trading system built on EM currency undervaluation to drive EM exports and economic growth, a shock equivalent to a magnitude 9.5 earthquake would occur. It would signal the opening shots in open economic warfare, whereby the DM would fight back to reclaim its economic growth ceded under the WTO. For EM economies grown fat on a diet of currency depreciation, a tsunami of incalculable proportions would wash ashore that wipes out their current economic model. In one fell swoop, such action would realign global growth, enabling the DM to reclaim a portion of its growth lost to trade. And, as the DM forced EM Currencies towards fair value, not only would trade realign, but Investment would shift back to DM markets, as manufacturers could once more compete globally. With a Plaza Accord 2019 ahead, the world stands poised on the cusp of a major realignment of economic growth. For the US and the other Developed Markets, economic growth will finally return to the levels of the 1980s and 1990s. But for the Emerging Markets, difficult times lie ahead as they adjust to a less generous world in which they must fundamentally grow and support their own economies. (Data from the Federal Reserve coupled with Green Drake Advisors analysis.)

Confidential – Do not copy or distribute. The information herein is being provided in confidence and may not be reproduced or further disseminated without Green Drake Advisors, LLC’s express written permission. This document is for informational purposes only and does not constitute an offer to sell or solicitation of an offer to buy securities or investment services. The information presented above is presented in summary form and is therefore subject to numerous qualifications and further explanation. More complete information regarding the investment products and services described herein may be found in the firm’s Form ADV or by contacting Green Drake Advisors, LLC directly. The information contained in this document is the most recent available to Green Drake Advisors, LLC. However, all of the information herein is subject to change without notice. ©2018 by Green Drake Advisors, LLC. All Rights Reserved. This document is the property of Green Drake Advisors, LLC and may not be disclosed, distributed, or reproduced without the express written permission of Green Drake Advisors, LLC.