Currency Wars Part V: The End to EM Devaluations

“As one might expect, introducing market power on both sides also introduces a new issue: the possibility of strategic trade policy. In general, strategic moves may be defined as actions that by themselves work to the strategic player’s advantage. The classic example from industrial organization is investment in excess capacity by a firm in order to deter entry by new competitors: the excess capacity viewed in isolation lowers the firm’s profits, but the effect on the behavior of firms that would otherwise have entered makes the expense worthwhile. In the trade policy context, the now standard example is that of an export subsidy that would ordinarily lower national welfare but that may raise welfare if it has a deterrent effect on foreign competition.”

Trade Policy and Market Structure

Chapter 5: Strategic Export Policy

By Elhanan Helpman and Paul R. Krugma

MIT Press, 1989

“Our primary findings may be summarized as follows. First, the Ricardian theorem of comparative advantage holds in the two-country world even if the preferences are different across countries. Second, in the case of incomplete specialization, local indeterminacy emerges under milder conditions, as compared to Drugeon (1998) and Nishimura and Shimomura (2006). Third, in the case of complete specialization, the relationship between tariffs and economic growth is ambiguous. When the Home country specializes in the investment (respectively, consumption) goods, a sufficiently higher rate of tariffs on the consumption (respectively, investment) goods reverses the trade pattern in the long run and decreases economic growth when the productivity coefficient of the investment goods in the Home (respectively, Foreign) country is larger than the threshold. However, economic growth is increased when the productivity coefficient of the investment goods in the Home (respectively, Foreign) country is smaller and in the Foreign (respectively, Home) country is larger than the threshold. Finally, tariffs increase (respectively, decrease) the long-run welfare in the Home country when it specializes in the investment (respectively, consumption) goods…

[T]he reason for the effect on long-run welfare is simple. The long-run welfare in the Home country is increasing in the ratio of consumption between the Home and Foreign country. When the Home country specializes in the investment goods, tariffs on the imported consumption goods increase the ratio of consumption between the Home and Foreign country in the long run, thereby increasing long-run Welfare in the Home country.”

Import Tariffs and Growth in a Model with Habits

By Been-Lon Chen, Shun-Fa Lee, and Koji Shimomura

International Trade and Economic Dynamics, 2009

Editors, Takashi Kamihigashi and Laixun Zhao

When economic historians look back on the past 40 years to write their histories, they will focus on the massive undervaluation of Emerging Market (EM) currencies coupled with their ability to export high value goods to the Developed Market (DM) Economies. This combination allowed them to supercharge their economic growth, enabling them to grow at a rate unsustainable otherwise, as their domestic economies stood at a size and income level unable to absorb the goods they produced. Through exporting goods, they developed a critical mass of industry that drove upward their income levels, putting their domestic markets in a position to absorb larger and larger components of the goods they produced and to continue to invest in more productive capacity, further boosting their Investment. In fact, unbeknownst to the citizens of the DM, the EM exceeded the size of the DM in 2009, never to look back, given its higher growth rate.

For the DM, this increased production overseas initially increased domestic welfare, as low value commodity inputs were outsourced, lowering prices to the average citizen. But, as with anything, any good idea, taken to an extreme, becomes a bad idea. And taken to an extreme is exactly what occurred here. From 1999 to 2018, high value goods production moved offshore at a rapid pace. As a result, for the average citizen, high paying jobs moved overseas and were replaced by low paying jobs. The decrease in income lowered the average citizen’s standard of living well in excess of the lower prices they could enjoy on the imported goods they no longer could afford. In addition, with Investment taking a large hit, economic growth slowed, hurting the citizen’s even further and harming the DM governments’ abilities to respond to these problems, as tax revenues did not grow at projected rates.

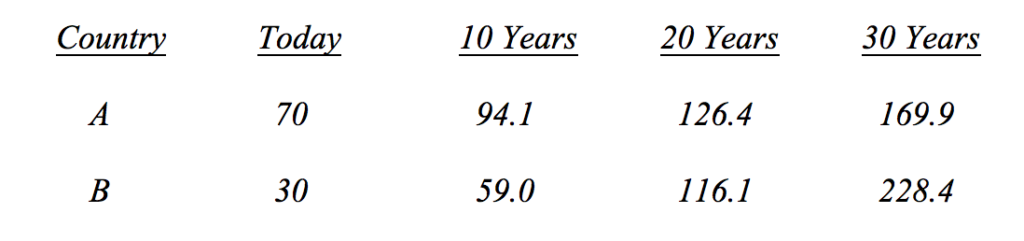

A simple thought experiment illustrates what occurred over the past 40 years. Imagine two countries growing at different rates. One possesses a GDP of 70 and the other a GDP of 30. Imagine that the country with a GDP of 70 grows at 3% but the country with a GDP of 30 grows at 7%. Here is what occurs over the long run:

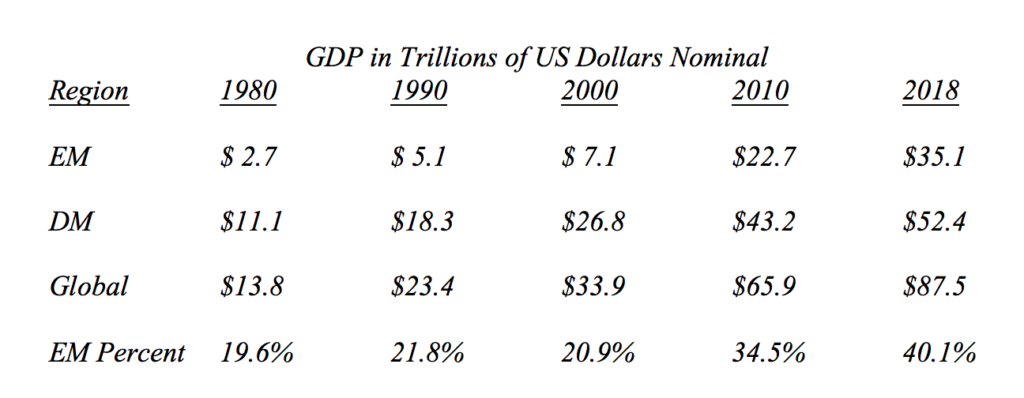

As is clear from the example, the different growth rates lead to Country B becoming 34% larger over 30 years, even though it started out 57% smaller. For those in the financial field, this example just illustrates the Law of Compounding over the long term. Now let’s apply this to the Emerging Markets compared to the Developed Markets. The first table below shows the data in Nominal Dollars, care of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In other words, it does not adjust in any way, shape, or form for the massive undervaluation of the Emerging Market currencies, which understates the true size of their economies relative to the Developed Economies:

Despite not adjusting for the currency undervaluation, the table makes clear the EM continues to gain on the DM. In fact, the EM now represents 40% of Global GDP up from 21% in 2000. Should the relative growth rates remain the same over the next 15 years, the Emerging Markets Economies will stand larger than the Developed Markets in Nominal US Dollars. So, from a political perspective, politicians can still claim that the Developed Economies reign supreme in the global order, even if that supremacy is going away. They may also use this to justify still a certain number of policies in regards to trade and financial aid, which the data below might call into question.

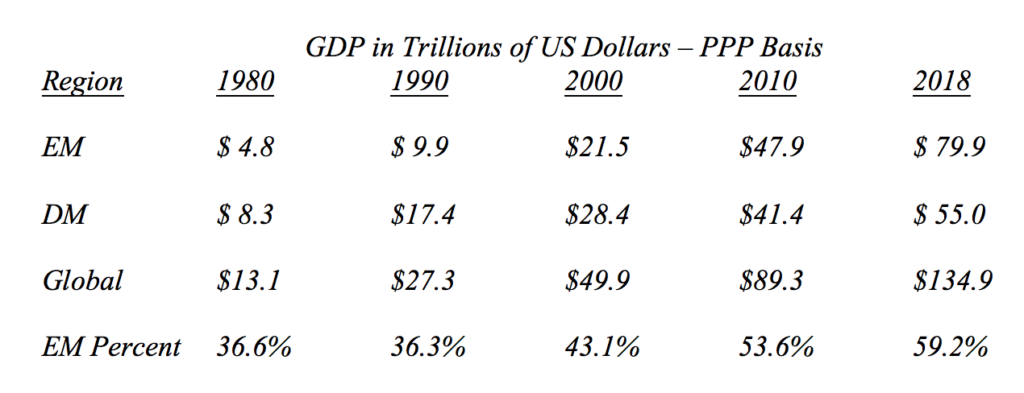

Now let’s correct this table for the massive EM currency undervaluation, using Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), and look at the real size of the EM Economies compared to the DM Economies. As the IMF data below demonstrate, a different story appears:

In fact, it might be called a Tale of Two Cities. As the PPP table demonstrates, the real size of the EM Economies stands 45% larger than the DM Economies and they now comprise, in real terms, almost 60% of the Global Economy. Now, given this real world data from the IMF, how should the Developed Economies act in order to enable their economies to participate in the higher growth that the Emerging Economies enjoyed over the past 30 years? Should they follow the same policies that dominated economic and foreign policy and that caused their economies to shrink significantly relative to the global economy? Or should they adopt something new? One might think new policies that produce a better result should become the focus given the data. (For those who wish to view the IMF data on their own, it is available at http://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/datasets/WEO/1where the IMF conveniently provides the data for download in Excel tables.)

Unfortunately, the current public perception in the US, on the make-up of the Global Economy, appears stuck in the view of the globe established at the end of World War II, in 1945, when the US stood astride the globe as the dominant economic power. The average citizen in the US possesses no knowledge that China became a larger economy than the US in 2014, when measured on a PPP basis. Nor do they understand that the EM economies dwarf those of the West and continue to grow much faster. This unfortunate state of affairs appears right out of a children’s fable, The Emperor Has No Clothes, with mainstream politicians and the media taking on the role of the crowd. No one in the crowd appears willing to tell the truth, even though they think it, as they are blinded by words of the Emperor and his advisors or, in this case, beholden to those whose interests they serve by acting blind to the truth. Thus, they fail to openly recognize the reality of today. Then a small child, who only knows what he sees, speaks up saying, “The Emperor has no clothes.” Once the child states the truth, all realize he is correct and that the Emperor stands naked for all to see.

For the Developed Economies, the little boy appeared in the form of Donald Trump. And while the majority of the media and most professional economists continue to have difficulty seeing that the Emperor stands naked and put their hands over their eyes so they don’t have to see the nudity, the public at large appears to recognize this reality. And once this reality forces itself upon decision makers and the media that like to shape public opinion, then a different set of policies focused on a much better economic result for the US and other DM economies must become the focus. When countries such as China, India, Indonesia, Brazil, South Korea, Mexico, Turkey, Malaysia, Iran and others all possess 1%+ PPP Global GDP or close to it, then policies must reflect these facts. For EM Economies that enjoy unfettered access to the US and other DM markets for their goods coupled with the ability to depreciate their currencies at will with no consequences, that era appears set to fade into history. This change began with Act I, a pending restructuring of trade agreements by the US over the past year. And while Act I focuses on changing the terms of engagement through access to its markets, in order to protect its economy and ensure fair treatment, Act II in this play approaches. This Act will address the Currency War waged on the US and other Developed Economies over the past 30 years. It will only allow access to its markets if other countries maintain the value of their currencies. It will treat currency devaluations as de facto tariff moves. It will move to cut off those offending parties. And, in extremis, it will intervene in the currency markets to ensure US and DM products and services remain globally competitive. And, in doing so, this change in policy will create The End to EM Devaluations as the Developed Economies explicitly recognize the massive change in the world over the past 40 years. (Data from the IMF coupled with Green Drake Advisors analysis.)

Confidential – Do not copy or distribute. The information herein is being provided in confidence and may not be reproduced or further disseminated without Green Drake Advisors, LLC’s express written permission. This document is for informational purposes only and does not constitute an offer to sell or solicitation of an offer to buy securities or investment services. The information presented above is presented in summary form and is therefore subject to numerous qualifications and further explanation. More complete information regarding the investment products and services described herein may be found in the firm’s Form ADV or by contacting Green Drake Advisors, LLC directly. The information contained in this document is the most recent available to Green Drake Advisors, LLC. However, all of the information herein is subject to change without notice. ©2018 by Green Drake Advisors, LLC. All Rights Reserved. This document is the property of Green Drake Advisors, LLC and may not be disclosed, distributed, or reproduced without the express written permission of Green Drake Advisors, LLC.