The Coming Bond Storm, Part 1

The Coming Bond Storm, Part 1: That 1980s LBO Game Again, Repurchasing to the Poorhouse, & Loving That Covenant Lite

“Financial institutions tend to assume that risk diversification – a classic portfolio principle of financial institutions – protects them sufficiently from the negative impact of credit deterioration. In addition, credit risk is blurred by increasing recourse to credit guarantees and insurance. In today’s world, institutional lenders and investors take false comfort that their enlarged securitized holdings allow them to make quick adjustments to changes in credit conditions.

For the system as a whole, however, this is impossible. Any single bank or investor can sell off assets to others and raise cash in an emergency, but that means others must be willing to acquire the assets. If everyone is trying to raise cash at the same time, no one will be successful, because there will be no buyers.”

Chapter 3: Dangers in the Rapid Growth of Debt

Interest Rates, the Markets, and the New Financial World

By Henry Kaufman, 1986

“There are Trading Sardines and then there are Investment Sardines. You better know which one you have before you open the can.”

Old Wall Street Saying

For those of us who lived through the 1980s, Wall Street roared along. First came a huge bond and equity bull market, as the country recovered from the inflation of the 1970s. At the same time came the advent of mortgage backed securities. These were swept along as home prices shot upward as US 10 Year Treasury interest rates fell from over 15.0% in 1981 to less than 7.5% in late 1986, enabling borrowers to pay more and more for the same residence. In addition, companies rushed to break ground on commercial buildings and order trains, cars, and planes as the Tax Reform Act of 1986 put an end to many of the tax shelters that these drove. Then in the late 1980s, LBOs (leveraged buyouts) and corporate takeovers exploded, as raiders and greenmailers and new merchant investment banks rode to the fore with the newly invented junk bonds, care of Michael Milken and Drexel Burnham Lambert. While the 1987 crash interrupted the party temporarily, when it became apparent this was a stock market event not an economy event, the party roared on to new heights, culminating in the epic buyout struggle over RJR Nabisco. As the RJR saga demonstrated, there existed no company too big nor a price too high to pay. And this type of approach replicated itself through the markets as company after company became either a buyout target or ripe pickings for a corporate raider. The multiples paid for companies reached new heights using linear or exponential financial projections to justify the prices paid, with little if any thought to what could go wrong. While the party lasted, Wall Street enjoyed the Roaring 1980s. Of course, this all came crashing down as the Federal Reserve raised interest rates, increasing the Effective Fed Funds Rate from 6.5% in March, 1988 to 9.8% in May, 1989. In fact, the Federal Reserve, realizing its mistake in tightening so quickly, lowered rates rapidly, but not rapidly enough, bringing the Effective Fed Funds Rate down to 8.15% by the time the Recession began in June, 1990.

The hangover rivaled the party. Housing prices fell 25% or more in major markets between 1987 and 1993. In some markets, such as Las Vegas, prices fell over 50%. In addition, in cities such as New York, condos which went for $275,000 in 1987 could be purchased for as little as $110,000 in 1993. Banks went bust, producing the S&L crisis, and mortgage securities collapsed. In addition, commercial buildings, which possessed a massive oversupply due to the rush to build prior to the 1986 Act tax deadline, saw occupancies drop and rents collapse, crushing the cash flow for the buildings. This put many of these buildings in the hands of insurance companies, that were the major underwriters of the debt, with massive losses threatening their solvency. In the junk bond market, today known as “high yield”, prices collapsed as the recession hit company financials. Numerous companies could not pay their interest bill. And due to the lack of buyers in the markets, even strong junk credits that could meet their interest and pay off the bonds at maturity, such as Duracell, the consumer battery manufacturer, traded for $0.50 on the $1.00. Quite a debacle one might say.

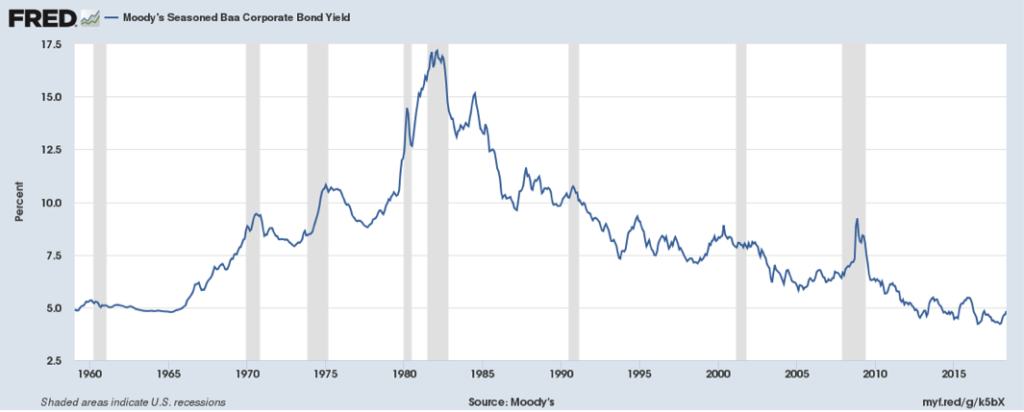

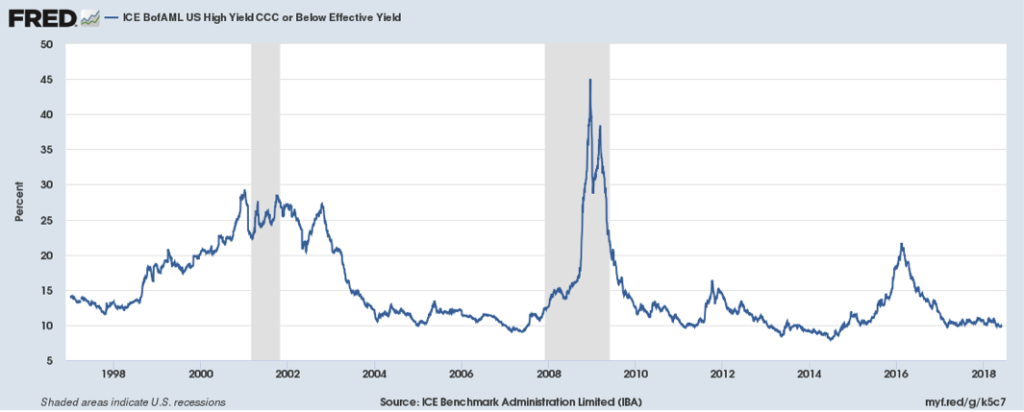

Today, some of the same practices that ended so badly 30 years ago appear in play, with new descriptors to protect the guilty. Valuations in M&A transactions have soared, along with the drop in rates. If you can finance it, you can justify it. Thus, not only are LBO shops (now known as Private Equity or PE) paying very healthy multiples of EBITDA and EBIT, but public corporations joined the game, much as in the late 1980s. (EBITDA stands for Earnings Before Interest Taxes Depreciation & Amortization while EBIT stands for Earnings Before Interest & Taxes.) For example, a company just announced a transaction for 13.5x EBITDA for a competitor. This works out to 18.5x the target’s EBIT producing a 5.5% initial return on the capital deployed. The problem with such a low return, even assuming “synergies” that increase the initial return to 7%, comes down to the cost of money and things that go bump in the night. Let’s first approach the cost of money. As the below charts demonstrate, the cost of money can vary quite a bit. The first chart covers BAA Yields, for decent quality corporate borrowers, while the second chart covers CCC or Below Yields, what is colloquially known as High Yield or, in the vernacular, Junk:

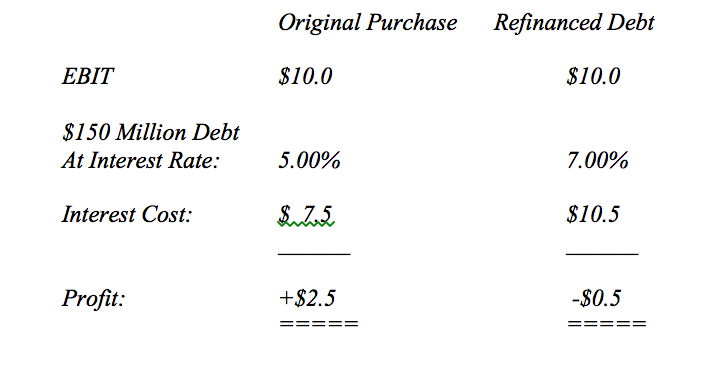

For borrowers in the 1960s, who came off a similarly low period of interest rates, things did not turn out as expected. Baa Interest Rates rose from below 5% in 1965 to almost 7% in 1968. They then took another leap forward to over 9% by mid-1970. Companies that financed with typical 5 Year or 7 Year financing faced a shock when it came time to refinance their debt as costs almost doubled. Suppose, a company just paid 18.5x EBIT and funded it 80% with debt. What happens when rates rise 2% on the acquisition? The following table demonstrates the issue:

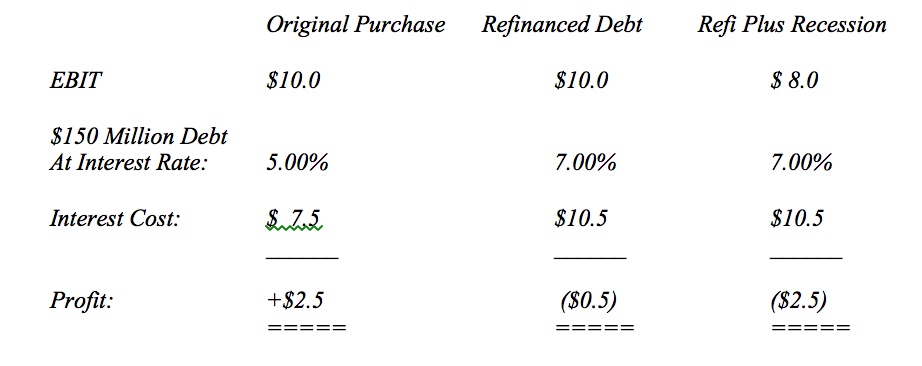

As the above table makes clear, profit becomes an object in the eye of the beholder. Now let us suppose further, that something comes along called a Recession, a thing that goes bump in the night. In a garden variety Recession, profits fall 20% – 25%. This would make the above table look like the following:

And this assumes that the credit rating does not fall below investment grade of BBB. Should the firm possess cash flow difficulties in covering its interest tab, markets would demand a much higher premium for taking on the risk of the firm. In other words, rates would increase in an exponential manner. And instead of paying 7% on its debt, the firm could face a rate of 10% or higher. For those nostalgic folks who currently want to replicate, Again, the pathway blazed by Mr. Milken and Drexel Burnham Lambert in That 1980s LBO Game, life will get interesting as the Federal Reserve herds the economy towards a Recession over the next few years.

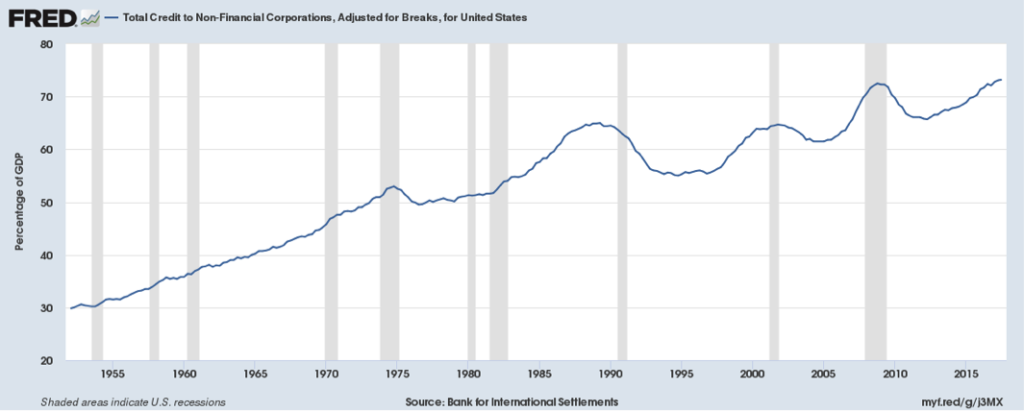

While not all corporations threw caution to the wind in their acquisitions, another whole segment focused on repurchasing copious amounts of stock while putting large amounts of debt on the balance sheet. This use of corporate cash focused on reducing the shares outstanding for the significant options companies granted to their executives. Thus, instead of investing in productive assets that could earn a return on capital and service the debt currently and in a downturn, companies chose to add debt without any way to service it. As a result, over 48% of Investment Grade Debt is rated BBB today up from 32% in 2009, despite 10 years of economic growth. This rating stands only one notch above Non-Investment Grade. Furthermore, Non-Financial Corporate Debt to GDP stands at record levels:

None of this bodes well should something go bump in the night for the US economy. But if everyone is doing it, it must be correct.

However, there does stand a difference between the largest public companies and their smaller brethren. Their smaller brethren, such as the companies found in the Russell 2000, increased their spending significantly this year due to the benefits from the tax cut passed last year. In fact, small companies raised their Capital Expenditures to Sales levels back to levels seen only early in the economic recovery, in 2012 and 2013, and during their peak spending years in the prior recovery, in 2006 and 2007. Small companies only spent more relative to sales back in 1998 and 1999. Given the assets put in place, they will stand in better stead than their larger brethren in a downturn. So, where are large companies spending cash not spent on capital expenditures or acquisitions? Massive Stock Buybacks. In fact, these companies stand on track to buyback a record amount of stock in 2018. At the same time, the large companies in the S&P 500 continue to invest at Capital Expenditure to Sales rates reminiscent of recession levels. In simpler terms, many of the companies in the S&P 500 appear well on track to Repurchasing To The Poorhouse. (For the deleterious impact on the US economy of these policies, see What’s Good For GM, Is Not Good For America: The Problem of Capital Investmentpublished January 31, 2015, Buybacks, De-Equitization, and The Hit to Capital Formationpublished December 31, 2015, and What’s Good For GM, Is Not Good For America: The Carrot and The Stickpublished on October 31, 2017.)

However, while corporations lusted after debt, investors stand close behind. Investors sent trillions into bond funds over the past several years just as long term interest rates stood at record lows last seen during the Great Depression. Their reach for yield became so strong, they accepted Covenant Lite Bonds and Loans. For those unfamiliar with the term “Covenant Lite”, one might consider it equivalent to a swear word for the debt investor. Effectively, a Covenant Lite bond or loan removes key protections for the investor from the indenture, the long legal document that dictates the bond or loan owner’s rights. In other words, when the you-know-what hits the fan, the debt owner may find the usual claims on a company’s cash flows and assets don’t exist. And the bond or loan issued at 100 cents on the dollar could end up trading significantly lower, wiping out any interest the investor received and then some. Covenant Lite Bonds now comprise 75% of Total Bond Issuance by corporations and 74% of Leveraged Loans Outstanding, up from less than 10% in 2009. In addition to these standard Covenant Lite bonds, investors gobbled up junk bonds that also contained Covenant Lite provisions. For an example of the issues investors face in a downturn, the WeWork bond offering stands front and center. The company lost over $900 million last year and had negative cash flow of ~$775 million. While it had ~$2 billion in cash on the balance sheet at year end, given projected losses, the company clearly felt this cash cushion inadequate and raised another $700 million through a bond offering in April. All three major rating agencies awarded the bonds ratings well into junk bond territory. And, if in a recession, as seems likely, a portion of its short term lessors decide to terminate their leases on 30 days notice, as allowed, Cash Flow would come under more pressure as the long term leases the company signed obligate it to send monies out the door regardless of the occupancy of its facilities.

With this type of issuance, today’s Covenant Lite Bonds, Leveraged Loans, and Junk Bonds have come to resemble those of the late 1980s. At that time, it was clear that numerous companies could barely cover or not cover at all their interest bill in good times, let alone bad. And, of course, this was covered up by the trading between institutions, such as Lincoln Savings & Loan and Columbia S&L, whereby loans were moved from one set of books to another at predetermined levels, to maintain the illusion of value and not recognize the true losses. Or, as was seen more recently during the early stages of the housing debacle in 2008, banks kept mortgages and mortgage securities on their books at values consistent with the loan issuance value or the initial mortgage security issuance valuation, as opposed to marking to market loans and securities to account for the massive defaults occurring in the marketplace. Curious how institutions try to save their own skins. In both cases, only when the regulators stepped into the market, to force the recognition of economic reality, did the institutions involved recognize on their books the losses they had incurred. Until this occurred, they claimed “plausible denial” that they possessed an issue. Ultimately, all that is going on today resembles that old Wall Street saying “There are Trading Sardines and then there are Investment Sardines. You better know which one you have before you open the can.” For those trolling in Covenant Lite waters, it appears they are fishing for Trading Sardines. But for the companies issuing those securities, it is Loving That Covenant Lite. (Data from public sources, Jefferies, and The Federal Reserve coupled with Green Drake Advisors analysis.)

Confidential – Do not copy or distribute. The information herein is being provided in confidence and may not be reproduced or further disseminated without Green Drake Advisors, LLC’s express written permission. This document is for informational purposes only and does not constitute an offer to sell or solicitation of an offer to buy securities or investment services. The information presented above is presented in summary form and is therefore subject to numerous qualifications and further explanation. More complete information regarding the investment products and services described herein may be found in the firm’s Form ADV or by contacting Green Drake Advisors, LLC directly. The information contained in this document is the most recent available to Green Drake Advisors, LLC. However, all of the information herein is subject to change without notice. ©2018 by Green Drake Advisors, LLC. All Rights Reserved. This document is the property of Green Drake Advisors, LLC and may not be disclosed, distributed, or reproduced without the express written permission of Green Drake Advisors, LLC.